After their plane crashed and they were stranded in the snowy wastes of the Andes mountains in Argentina, Roberto Canessa and the other survivors of Flight 571 were on the brink of starving to death.

Meagre items of food and drink salvaged from the wreckage — chocolate, nuts, crackers, jam, fruit and some bottles of alcohol — had run out and no vegetation or animal life could be found at the elevation of 11,710ft (3,570m).

Their hunger became so all-consuming and desperate that some attempted to chew strips of leather from luggage and eat foam from the broken aircraft’s seat cushions.

As they grew weaker, and the chances of rescue grew more distant, the survivors gradually came to realise what the next step had to be if they were to stay alive.

It was something that, at first, was too terrible to contemplate.

The bodies of 18 of their friends, relatives and members of the flight’s crew were frozen in the snow and the passengers’ only chance of survival lay in the unthinkable: resorting to cannibalism and eating the bodies of the deceased.

Ten days into their ordeal, after much soul-searching and praying for guidance, some of the passengers — including Canessa — used a razor blade and shards of glass to cut strips of skin, muscle and fat off the frozen bodies, and forced themselves to swallow small mouthfuls.

‘Each of us came to the decision in our own time and consumed the food when we could bear to,’ recalls Canessa, speaking to the Mail from his home in Montevideo, Uruguay.

‘It was a process,’ he says. ‘At first, I thought that I could not take advantage of my dead friends’ bodies. Then it became something that was natural, almost an everyday routine, because the food was part of the fuel for getting out of there. I chose to live. I am proud of what I did.’

This remarkable true story is told in the new film called Society Of The Snow, currently trending in the top five shows on Netflix.

There have already been books, documentaries and a 1993 film, Alive, about one of the most thrilling and extraordinary survival stories in modern history.

But this new version by Spanish film director J A Bayona, is the nearest anyone has come to being able to understand what he and the other passengers went through, says Canessa.

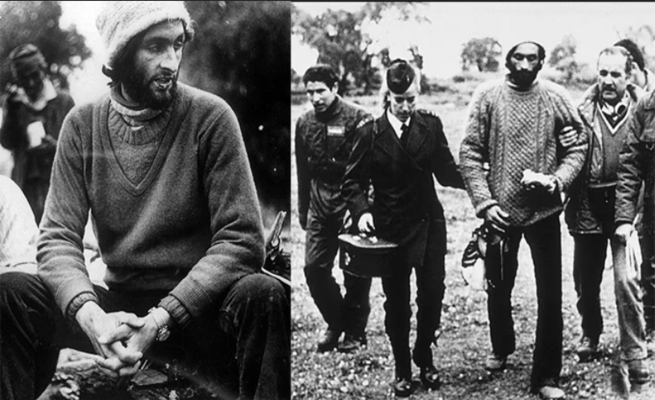

Canessa was a 19-year-old medical student and one of 45 passengers and crew — including 18 members of his Old Christians rugby team and their family and friends — aboard a chartered Uruguayan Air Force flight flying from Montevideo in Uruguay to Santiago, Chile, in October 1972.

A storm had forced the group to spend the night in Mendoza, Argentina, before the plane took off again on October 13 for what should have been a 90-minute journey. But, due to fatal combination of turbulence and pilot error, the plane clipped the top of a 15,000ft (4,572m) peak, shearing off both wings and the tail. The remaining part of the fuselage then slid down a glacier at over 200mph before coming to rest in the ice and snow.

Three crew and nine passengers died instantly, and another six perished in the following days due to their injuries and the sub-zero temperatures.

Canessa, now 70 and one of the world’s leading paediatric cardiologists, vividly recalls the terrible moment of the crash and then the shock and despair of finding themselves stranded in the beautiful, but hostile, Andes mountains.

‘I saw the mountain in front of us and remember the plane trying desperately to climb and gain altitude, and then I felt a violent blow,’ he says. ‘I thought “this is it”… and then the plane stopped very abruptly because it reached the bottom of the valley.’

Initially, he was confused, Canessa says: ‘I couldn’t believe I was still alive, and I thought I had to get out quickly because the emergency services would be coming to help us. Then I made my way to the back of the plane and realised the tail was gone.

‘I looked out and we were in the middle of the most desolate scenery that you can imagine.’

Canessa and others who were unhurt began to check who was dead and who was alive and to treat the injured as best they could. The freezing temperatures were almost unbearable, and they frantically opened suitcases in search of jackets and sweaters.

It was hard to breathe because the air in the endless white vista was so thin, Canessa says.

His friend Nando Parrado, a 22-year-old business student, had a serious head injury and was initially presumed to be among the dead.

His sorrowful friends laid him out in the snow with the other bodies and he remained there without shelter or water, in a coma, for nearly four days, a fact that saved his life because the low temperatures prevented his brain from swelling and killing him.

Eventually, one of his friends noticed signs of life and brought him into the fuselage.

When Parrado awoke, Canessa had to break the news to him that his mother Eugenia was dead, and his 19-year-old sister Susy was gravely injured. She died on the eighth day, with her heartbroken brother holding her hand.

At first, the survivors resolved to stay where they were. Help was surely on the way, they thought, as they listened for updates on the tiny transistor radio one of the survivors had with him.

But on day eight they heard the news they dreaded.

After multiple rescue planes failed to spot the white fuselage in the snowy landscape, the search was being called off.

‘There had been a huge dilemma, to climb [out of the valley] and maybe die climbing, or to wait for the rescue which was the most sensible thing to do,’ says Canessa. ‘When we heard on the radio that the search had been called off, one of us said “the dilemma’s over. We must get out by ourselves because nobody’s coming to help us”.

‘In a way, it helped us make the decision.’

As a medical student, Canessa was one of the first to realise that the dead passengers whose bodies were preserved in the ice and the snow outside the plane where the survivors were sheltering, were a source of protein and could provide life-supporting sustenance, as they waited for conditions to improve so they could attempt their journey.

He thought about the implications deeply, he says, and decided that if he had been one of the passengers who perished he would have been happy if others had consumed his body to stay alive.

‘Instead of rotting in a grave, my body could be life for my friends,’ he says.

The film shows the survivors’ torment as they discuss whether or not to feed off the bodies, with some of them pledging their own corpses to the others if they died. On the ninth day, Canessa and three others stripped the clothes from a body — avoiding looking at the dead man’s face — and removed strips of frozen flesh, laid them out and then swallowed them. Others also began to eat but some survivors took longer than others to overcome their revulsion.

Numa Turcatti, who is shown as the narrator of the film and who is played by actor Enzo Vogrincic, died because he could not bring himself to eat more than a few morsels, even though he was supportive of the others doing so.

On October 29, some 16 days after the crash, fate dealt the tragic group another terrible blow when an avalanche struck, burying the fuselage in which they were sheltering in a wall of ice and snow. Eight more died.

In his 2016 memoir I Had To Survive, Canessa describes how he and others frantically worked to clear snow out of the mouths and noses of their friends. He scrambled to save his boyhood friend Daniel Maspons, who had been sleeping beside him in the fuselage.

‘Desperately, I clawed through the icy snow, scraping at it until my nails bled… I swept the snow away from his face and out of his mouth and leaned in to listen for his breath. But there was only silence. My beloved friend was dead,’ he wrote.

It took the remaining survivors three days to dig themselves out.

The makeshift hammocks, spare clothes and blankets the survivors had made from the aircraft’s seat covers and which gave them some comfort had been lost. The frozen bodies outside, that had been keeping them alive, were swept away and they had no source of food. They had no choice but to steel themselves and eat the raw flesh of the newly dead.

On December 12, two months after the crash, the weather had improved sufficiently for Canessa and Parrado — the heroes of the film — to contemplate the dangerous trek out of their living nightmare. They had no climbing experience, no mountaineering equipment or protective clothing and at times they found themselves up to their hips in snow, clinging onto cliff faces and nearly falling into canyons.

In ten arduous days, they trekked 38 miles, carrying supplies of frozen human flesh and sleeping bags made from scraps of the plane’s insultation material, with them.

‘Both of us knew we could fail but we put those feelings aside,’ recalls Canessa. ‘Every step we took was a step towards life.

‘When we got very tired and thought we couldn’t go on, we looked back and saw how much we had already done.

‘It’s something I learned that I’ve taken with me for my whole life… when you feel frustrated, look where you have come from and how much you have achieved and that means you are capable of achieving more.’

Finally, they began to see evidence of civilisation, and what Canessa refers to as ‘the golden moment’ when they spotted a peasant worker on horseback on the other side of a raging river, as night began to fall.

In the film, Parrado digs a hole and reverently buries a small cotton bag of frozen flesh in the earth after he is rescued and prays over it.

When news broke of their incredible survival, the Chilean Air Force scrambled helicopters and Parrado led them to the crash site, to scenes of wild jubilation.

The men’s escape from the jaws of death created a sensation, with the media calling it a ‘miracle.’

Almost immediately, however, questions began to be asked. How could they have survived 72 days in a hostile environment where nothing grew or lived? Then pictures of a half-eaten leg, taken by members of the Cuerpo de Socorro Andino (Andean Relief Corps) were printed in Chilean newspapers, and the terrible truth became known.

The survivors held a solemn and emotional press conference, where, through a spokesperson, they explained their ‘pact’ and what they’d had to do to survive.

Canessa says he later spoke personally to the families of the victims and received an outpouring of support.

‘Everyone has their opinion good or bad about what we did, but I chose to live. I have never been unsure about what I did,’ explains Canessa.

Nowadays, Canessa points out that we transplant organs like kidneys or hearts after death to save lives. ‘In the same way, we used the bodies of the dead to keep living,’ he says.

The remains of those who died were buried in a mass grave at the crash site and a memorial erected. The carcass of the fuselage was doused in fuel and set alight.

Canessa returned to medical school, married and had three children and is now a contented grandfather. He says the life-or-death experience was a catalyst for the way he has lived his life, and his aim has always been to honour the sacrifices of those men and women who did not return from the mountains.

‘I couldn’t look at the relatives who lost their family members and have them see me as a fool,’ he continues. ‘I made a commitment to lead a decent and valuable life in tribute to my friends and to cherish the time that I have been given that the others didn’t have.’

Parrado also went on to live a successful life. He married, had two daughters and three grandchildren, worked in the family’s hardware business, became a professional race car driver and then ran a television station in Uruguay. The 72-year-old is now retired but travels the world as a motivational speaker.

The survivors — two have since died — still meet up every year in December, the month they were rescued. This year was the 51st anniversary. The survivors and family members of those who died worked closely with the makers of Society Of The Snow and were given private previews of the film.

They all agree that the film is an honourable depiction of the ordeal they and their loved ones went through.

‘This film is about the human spirit. It’s a story about normal people faced with terrible circumstances and how hope, determination and camaraderie produced incredible results,’ says Canessa.

The elderly doctor recalls returning to the crash site on the mountain with his grown children.

‘I felt that my friends were still there in that beautiful wilderness, hugging me and kissing me and teasing me about my grey hair and my belly,’ he says, a tremor of emotion in his voice.

‘And they were all still young and beautiful and brave. – DailyMail